|

The following is a reprint of an article that appeared in the April 1916 edition of Bakers Review, a trade publication for commercial bakers. The National Biscuit Co. (N.B.C.) was the forerunner of Nabisco. Following the article is a timeline of company ownership from the archives of Kraft Foods, the current owner of Nabisco.

Some Reminiscences of a Lifetime

Spent in the Baking Business

By Thomas S. Ollive, Vice-President of the National Biscuit Co.

Editor’s Note: The N.B.C., official house organ of the National Biscuit Co., recently published the following from the pen of the man who is reputed to be the oldest biscuit baker in the country. The Illustrations as well as the story are of peculiar interest to cracker bakers of the present day.

Some people say that I am the oldest biscuit baker in the country and maybe I am. In any event, I started to bake biscuits at the age of fifteen and I have been in the biscuit business ever since. As I am eighty years old now, I am thus credited with sixty-five years spent in the industry. Some people say that I am the oldest biscuit baker in the country and maybe I am. In any event, I started to bake biscuits at the age of fifteen and I have been in the biscuit business ever since. As I am eighty years old now, I am thus credited with sixty-five years spent in the industry.

I was born in Liverpool, England, on May 17th, 1835. When I was ten years old our family came to America and my father started a small cracker factory in New York City. In 1850, when I was fifteen, I started to work for him.

New York, then, as now, was a large city, as cities went in that time, but it was confined to the lower or southern end of Manhattan Island. Fiftieth Street was far up-town and beyone that was open country. Had any one prophesied then that the city was destined to be the largest city in the world and that in fifty years it would have more than four millions of people within its borders, he would have been laughed to scorn.

Eight Cracker Bakers in New York City in 1850

The business of cracker baking in the country was also in its infancy. In the year 1850 there were but eight cracker bakers in New York City: Speir & Company in Pine Street; Sanford & Goodwin in South Street; J. T. Wilson & Company in Dutch Street; Johnson & Treadwell in Beekman Street; Erastus Titus in Washington Street; Parr & Company in Mott Street; I. & J. McGay in Forsyth Street and Joseph Bruen in Delancey Street.

All these bakers made the same line of goods with the exception of Joseph Bruen, who specialized in oyster or butter crackers. His product, made entirely by hand, was of unusual excellence and was used by all Oyster Houses, the then prevailing designation for restaurants and eating places. Each day he would deliver the crackers fresh from the ovens to his customers. Wearing a long-tailed coat and high silk hat, he would drive his two-wheeled cart about town making deliveries as ordered. The crackers were put up in cotton cloth bags, each bag holding seven pounds. “Joe” Bruen was a picturesque figure, a character indeed, whom everyone knew.

My earliest recollections go no farther back than 1850, at which time there were but five principal kinds of crackers manufactured; namely, the butter or oyster crackers, the soda cracker, the sugar cracker (ed. note - this was the term for cookies), the ginger snap and the pilot cracker (more commonly known as ship bread), this being made in large quantities to supply the sailing vessels, it being their only staple food for long voyages. I well remember helping to stock ships’ lockers with these crackers. The extra supply was carried in hogsheads and barrels. By far the largest part of the output of nearly all the old bakeries consisted of pilot crackers.

Hand labor was used exclusively in making the butter and sugar crackers, but we had machines to cut the soda and pilot crackers, making use of hand labor in mixing and preparing the dough. In those days we began to work at four o’clock in the afternoon, with the minimum amount of time for breakfast and dinner. I am glad to say, though, that this custom did not prevail long.

Butter crackers were made by taking one or two barrels of flour of the best grade and adding about fifteen pounds of butter and fifteen pounds of lard to each barrel. These ingredients were then mixed by hand in a wooden trough with the necessary amount of water and salt until the dough reached the proper clearness. Butter crackers were made by taking one or two barrels of flour of the best grade and adding about fifteen pounds of butter and fifteen pounds of lard to each barrel. These ingredients were then mixed by hand in a wooden trough with the necessary amount of water and salt until the dough reached the proper clearness.

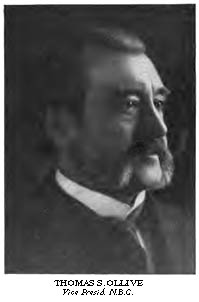

A canvas was then spread over the dough and it was treaded into a solid mass, after which it was taken to the “brake.” This consisted of a circular or square platform having a long stick (nicknamed a “horse”) attached to an iron swivel in the rear. The different workmen took turns in jumping upon this “horse” and so kneading the dough. It was pretty strenuous work.

When the dough had attained the right consistency it was cut by hand into squares, placed on a bench and cut again, this time into strips two feet long and two inches wide. These strips were shaped by hand into long thin rolls and these in turn were transformed into small balls a little larger than marbles by dexterous manipulation of the fingers. The balls were moulded on the table by the palm of the hand into the desired shape. In some cases they were placed on long wooden splints and set in the oven.

The process of mixing dough for pilot and soda crackers was identical with the process I have described, but the cutting was done by a machine worked by hand power. The baking was done on the bottom of the oven. Ginger snaps and sugar crackers were baked in pans. Crackers were delivered in barrels, boxes and seven-pound bags. We never carried stock.

In the spring of 1855 I went to San Francisco to become foreman for Deith & Starr, one of the two bakeries on the Coast. About the only product manufactured by these bakers was pilot crackers, made in the same manner as in the East. Deith & Starr, however, put out a soda cracker of superior quality, butter being the only shortening used.

Two years later I crossed the Sierra Nevada Mountains and located at Yreka in the beautiful Valley of the Shasta in Northern California, where I engaged in business for myself. On the backs of mules, at an expense of twenty cents per pound freight, I packed a cracker-cutting machine over the mountains. It was the first cracker machine ever seen in that territory.

At Yreka the only crackers we baked were soda crackers, which we sold at twenty-five cents a pound. We also baked pies, which we made with dried fruits. For these we received fifty cents apiece. Our flour we got from a mill in the Shasta Valley, at a cost of eight dollars per barrel, or four dollars a hundred weight. Our lard came from Oregon and cost twelve cents a pound. We had a small tile oven and we did all our own work.

There were wonderful opportunities in California for cracker bakers, but unfortunately my state of health forbade my remaining and so, in the Spring of 1860, I returned to New York.

The First Reel Oven

In New York I found that Mr. E. O. Brinckerhoff (a school teacher who had successfully graduated to the business of cracker baking) had moved his bakery in my absence from Madison Street to Grand Street and there completed the erection of the first reel oven, the invention of Hosea Ball.

This oven eventually proved successful, but only after the greatest of difficulties and a burden of expense which bankrupted Mr. Brinckerhoff. Ultimately, however, he prospered and paid every dollar he owed with interest at seven percent. Mr. Brinckerhoff was the first baker in New York City to produce a high grade soda cracker and because of it he built up a wonderful reputation.

On my arrival from the Coast I opened a “bake shop” of my own in New York City at 14th Street and Third Avenue. Shortly after the Civil War broke out and we who were engaged in the business of baking crackers were very busy making hardtack for the army. Those were busy times indeed.

In 1868 I became a member of the firm of Brinckerhoff & Company. Machinery was beginning to be improved and consequently to play a more important part in the production of crackers. Of course it also resulted in extending our list of products.

The old method of selling crackers through wagon drivers on a commission basis still prevailed, the era of the traveling salesman not having dawned. The commission to the driver was 20 per cent, no goods being returnable except by reason of fault in manufacture. Boxes, barrels and bags were all charged for. The firm name in stencil on the box or barrel was the only mark of identification. The average price of soda crackers to the drivers at that time was from six to nine cents per pound, dependent upon the market price of flour. The other varieties of crackers sold anywhere from ten to twelve cents per pound.

In 1872 the firm of Belcher & Larabee of Albany, New York, installed a set of English machines for cutting. At the same time they introduced English hard sweet biscuit of which the variety known as “Cornhill” became very popular, wholesaling at 18 cents per pound. Supply seldom equaled demand and it was often necessary to wait long periods for deliveries.

The First Dough Mixer

About this same time the dough-mixing machine also came into use. When the first machines were sent to this country from England, Mr. John Holmes accompanied them as the practical baker and he produced crackers of excellent quality, which became very popular and made him very successful.

In 1875 I took a trip to Europe, and while in Great Britain had the pleasure of a visit to the Carlisle Biscuit Factory at Carlisle, England. When I called, I stated by connections and my desire to learn their methods. I was received most courteously and was invited to make a thorough inspection of the factory, which I did. I found the methods of manufacture to be very efficient, but not superior to the methods then in operation on this side of the Atlantic.

The variety of biscuit products continued to increase. Some of the new varieties were fruit biscuit, water thin biscuit and a variety of sweet goods which came to be known to the trade as the “cookie line.” About this same time marketing methods for biscuit began to show changes, tin cans coming into prominence for the first time. The use of labels and registered names also came to have rapid growth.

In 1880 Mr. Holmes Left Larabee & Company and the firm of Holmes & Coutts was founded. Its best known product was Sea Foam Biscuit. In 1885 the firm of Vanderveer & Holmes was formed and began business in Vesey Street, making a specialty of labeled goods and extending the line of cookie varieties. Mr. D. M. Holmes about this time invented a machine for the cutting of soft dough which brought about a great advance in the manufacturing process. At this time, also, the jumble variety of biscuit came into prominence and popularity. In 1880 Mr. Holmes Left Larabee & Company and the firm of Holmes & Coutts was founded. Its best known product was Sea Foam Biscuit. In 1885 the firm of Vanderveer & Holmes was formed and began business in Vesey Street, making a specialty of labeled goods and extending the line of cookie varieties. Mr. D. M. Holmes about this time invented a machine for the cutting of soft dough which brought about a great advance in the manufacturing process. At this time, also, the jumble variety of biscuit came into prominence and popularity.

In 1890 the New York Biscuit Company was founded and from this time until the time of the formation of the National Biscuit Company in 1898, improvements in baking methods gradually increased.

The formation of the National Biscuit Company resulted in practically a new biscuit industry, so thorough was the revolution which took place. Crackers made their appearance in the dust, dirt, moisture and odor proof In-Er-Seal Trade Mark package. The products were given distinctive trade names. A country-wide advertising campaign was engaged in to secure national distribution, to tell people about crackers and the new idea of selling them, thereby to increase their popularity and their consumption. These and the other steps taken by the National Biscuit Company assured the progressive success of the industry. The formation of the National Biscuit Company resulted in practically a new biscuit industry, so thorough was the revolution which took place. Crackers made their appearance in the dust, dirt, moisture and odor proof In-Er-Seal Trade Mark package. The products were given distinctive trade names. A country-wide advertising campaign was engaged in to secure national distribution, to tell people about crackers and the new idea of selling them, thereby to increase their popularity and their consumption. These and the other steps taken by the National Biscuit Company assured the progressive success of the industry.

Nabisco Organizational Timeline

Compiled by Kraft Foods Archives Dept.

| 1889 |

Late in the year attorney William Moore forms New York Biscuit Company through the combination of the Bent & Company, Milton, Massachusetts; John Pearson & Son, Newburyport, Massachusetts; Wilson Baking Company, Philadelphia; Parks & Savage, Hartford, Connecticut; J.D. Mason & Company, Baltimore, Maryland; Burlington Bread Company, Burlington, Vermont; New Haven Baking Company, New Haven, Connecticut; Treadwell & Harris, New York.

It is incorporated in early 1890 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. |

| 1889-1890 |

With the assistance of attorney Adolphus Green the American Biscuit & Manufacturing Company is formed through the amalgamation of 40 Midwestern bakeries including Sommer-Richardson Baking Company, St. Joseph, Missouri; Aldridge Bakery and Bremner Bakery, Chicago; Carpenter & Underwood, Milwaukee; Dozier Baking Company, St. Louis; Langeles Bakery, New Orleans; and Loose Brothers, Kansas City.

Its headquarters is also in Chicago, Illinois. David Bremner is president.

United States Baking Company, with bakeries in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Pennsylvania is also organized with the assistance of Adolphus Green. Sylvester S. Marvin, prominent Philadelphia baker, is president. |

| 1898 |

National Biscuit Company (often referred to as N.B.C.) is established through the merger of American Biscuit & Manufacturing Company, New York Biscuit Company and United States Baking Company.

Its headquarters is located in Chicago, Illinois. Adolphus Green becomes president. |

| 1971 |

National Biscuit Company changes its name to Nabisco, Inc. |

| 1971-1982 |

Nabisco, Inc. purchases the pharmaceutical and men’s toiletries business of J.B. Williams Company in 1971. Aqua Velva shaving products is one of the J.B. Williams product lines that Nabisco acquires. Yankee Soap, the first shaving soap ever manufactured in America and the very-long-ago predecessor of what became Aqua Velva, was never owned by Nabisco. Nabisco sold the J.B. Williams Company – and Aqua Velva – in 1982. |

| 1981 |

Nabisco, Inc. merges with Standard Brands (founded in 1929) to become Nabisco Brands. The merger adds Planters nuts to the portfolio.

Life Savers Company is acquired by Nabisco Brands. |

| 1985 |

R.J. Reynolds merges with Nabisco Brands to form R.J. Reynolds Industries, creating the largest consumer goods company in the country. Brands added to the portfolio are, among others, A.1. Steak Sauce and Grey Poupon Mustard. |

| 1986 |

R.J. Reynolds Industries changes its name to RJR Nabisco Inc. |

| 1988 |

R.J.R. Nabisco is taken private by Hohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. At the time, it is the largest leveraged buyout ever at $26 billion.

In Canada, Nabisco acquires the Red Oval Farms cracker business from InterBake Foods. |

| 1989 |

The name R.J.R. Holdings Corp. is changed to RJR Nabisco Holdings Corp, the parent company of RJR Nabisco, Inc |

| 1995 |

R.J.R. Nabisco offers an initial public offering for 19.5% of Nabisco Holdings. Its food operations are conducted by its wholly-owned subsidiary called Nabisco, Inc. |

| 1999 |

Nabisco Holdings acquires Favorite Brands International (FBI). A few years earlier, FBI had acquired Kraft’s caramel and marshmallow business.

R.J.R. Nabisco spins off Nabisco Holdings Corp. A new holding company; Nabisco Group Holdings now owns 81% of Nabisco Holdings. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Holdings owns the tobacco business. Nabisco Group Holdings business is conducted by Nabisco Holdings (“Nabisco”), a wholly-owned subsidiary of Nabisco, Inc. |

| 2000 |

Philip Morris acquires Nabisco Holdings Corp. for $14.9 billion in mid-December. It is integrated into its Kraft Foods business in January of 2001. |

|